Return on equity

Return on equity (ROE) measures the rate of return on the ownership interest (shareholders' equity) of the common stock owners. It measures a firm's efficiency at generating profits from every unit of shareholders' equity (also known as net assets or assets minus liabilities). ROE shows how well a company uses investment funds to generate earnings growth. ROEs between 15% and 20% are considered desirable.[1]

Contents |

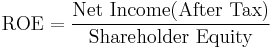

The formula

ROE is equal to a fiscal year's net income (after preferred stock dividends but before common stock dividends) divided by total equity (excluding preferred shares), expressed as a percentage. As with many financial ratios, ROE is best used to compare companies in the same industry.

High ROE yields no immediate benefit. Since stock prices are most strongly determined by earnings per share (EPS), you will be paying twice as much (in Price/Book terms) for a 20% ROE company as for a 10% ROE company.

The benefit comes from the earnings reinvested in the company at a high ROE rate, which in turn gives the company a high growth rate. The benefit can also come as a dividend on common shares or as a combination of dividends and reinvestment in the company. ROE is presumably irrelevant if the earnings are not reinvested.

- The sustainable growth model shows us that when firms pay dividends, earnings growth lowers. If the dividend payout is 20%, the growth expected will be only 80% of the ROE rate.

- The growth rate will be lower if the earnings are used to buy back shares. If the shares are bought at a multiple of book value (say 3 times book), the incremental earnings returns will be only 'that fraction' of ROE (ROE/3).

- New investments may not be as profitable as the existing business. Ask "what is the company doing with its earnings?"

- Remember that ROE is calculated from the company's perspective, on the company as a whole. Since much financial manipulation is accomplished with new share issues and buyback, always recalculate on a 'per share' basis, i.e., earnings per share/book value per share.

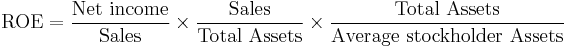

The DuPont formula

The DuPont formula, also known as the strategic profit model, is a common way to break down ROE into three important components. Essentially, ROE will equal the net margin multiplied by asset turnover multiplied by financial leverage. Splitting return on equity into three parts makes it easier to understand changes in ROE over time. For example, if the net margin increases, every sale brings in more money, resulting in a higher overall ROE. Similarly, if the asset turnover increases, the firm generates more sales for every unit of assets owned, again resulting in a higher overall ROE. Finally, increasing financial leverage means that the firm uses more debt financing relative to equity financing. Interest payments to creditors are tax deductible, but dividend payments to shareholders are not. Thus, a higher proportion of debt in the firm's capital structure leads to higher ROE. [1] Financial leverage benefits diminish as the risk of defaulting on interest payments increases. So if the firm takes on too much debt, the cost of debt rises as creditors demand a higher risk premium, and ROE decreases. [3] Increased debt will make a positive contribution to a firm's ROE only if the matching Return on assets (ROA) of that debt exceeds the interest rate on the debt. [4]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "Profitability Indicator Ratios: Return On Equity", Richard Loth Investopedia

- ^ http://www.answers.com/topic/return-on-equity Answers.com Return on Equity

- ^ Woolridge, J. Randall and Gray, Gary; Applied Principles of Finance (2006)

- ^ Bodie, Kane, Markus, "Investments"